Inherited Memories at Castelli Art Space

- artandcakela

- May 24, 2019

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 27

Shula Singer Arbel, Inherited Memories, Castelli Art Space; Photo Credit Betty Ann Brown

Inherited Memories: Shula Singer Arbel, Dwora Fried & Malka Nedivi

Castelli Art Space, Los Angeles through May 28

Curated by Peter Frank

Written by Betty Ann Brown Ghosts fill Castelli Art Space. A tall, columnar man stands in silent witness. Two children hover above a bunk bed of buttons. Shadowed faces shimmer behind curtains of time and loss.

The gallery is filled with powerful works by LA artists Shula Singer Arbel, Dwora Fried and Malka Nedivi. All three women are the children of Holocaust survivors. All three use their art to exorcise the demons of suffering and deprivation that were handed down from their forbears’ experiences of the devastating ordeal known as the Shoah.

Arbel creates graceful figurative paintings that echo photographs from the 1930s and’40s. Some are quite spectral: “When We Were Whole #1” is a portrait of five people–a couple with three children?–grouped inside a saffron surround. Their faces and clothes are indigo. And below them is inscribed “Chust 1933,” a reference to an Eastern European town decimated by the Holocaust. I ache for the loss of this ghostly family and, by extension, their community. Their faces shimmer in the liminal space between past and present, living and dead. I look at them quietly and think of Shula’s 94-year-old father who passed the day of the opening. Tears of grief wash Arbel’s face as she speaks to me about his death, and I think about all the survivors who are living and dying now and hope their memories will be recorded. American playwright Arthur Miller once said, “I think the job of the artist is to remind people of what they have chosen to forget.” Arbel must agree. She hopes that the exhibition “sheds light on the fact that trauma is passed down generationally.”

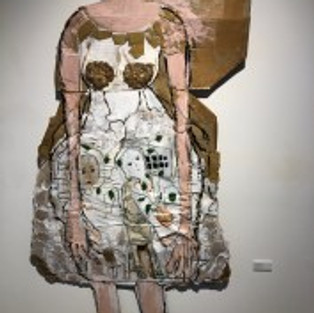

Dwora Fried’s miniature tableaux address the impact of the Holocaust on the psychological make-up of survivor families. Demonic specters hover in shadowed spaces, the bright plastic of dolls and other toys contrasting uneasily with darker tones, visually articulating the conflicts and contradictions that children must navigate in wounded homes. Fried also created a “human-scale” tableau for “Inherited Memories.”

Two nude children, portrayed by mannequins, stand on the top bed, their feet resting in a sea of vintage buttons. I look at the multitude of buttons and immediately think of the photograph of a veritable mountain of shoes from Dachau. There are images of piles of shoes from Auschwitz, Bergen Belsen, and Majdanek as well; the un-countable accumulations of personal attire, whether shoes or buttons, underscores both the magnitude and the personal, individual impact of the mass executions.

Dwora Fried, Inherited Memories, Castelli Art Space; Photo Credit Kristine Schomaker

Fried spent time in Austria, and her work is impacted by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud as well as by the horrors of war. In the miniature tableau “Pigeons”, a relatively large man, naked except for his military hat and evil countenance, holds a tiny baby in his lap. The sexual connotations are deliberate and deeply disturbing. Below the man is a living room-like space occupied by three female figures, two of whom are suspended upside-down from the ceiling like torture victims. On the far right is a photograph of a little girl (baby Dwora?) disappearing into the back wall. The artist has dressed her in fabric clothing and surrounded her with miniature furniture, from a lamp to a stool to a tiny teacup, transforming the tableau “box” into a middle class domicile. How does a family go from the Holocaust to “normal” life? What kind of domestic environment did baby Dwora–and, by extension, all of the children of survivors–grow up in?

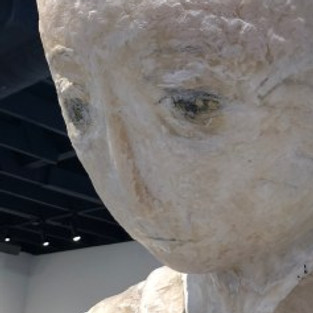

Malka Nedivi is a sculptor. She constructs human figures and house forms, using metal armatures covered in everything from paint to encaustic to plaster to fabric. She also does relief works on canvas. “Welcome Home” is a small relief portraying two ghostly figures. Both appear to be female. And both are strangely, hauntingly surreal. One sits, the other hangs, her arms and legs ending in strange pods and evoking animal appendages more than human limbs. At the beginning of his seminal 1928 work Nadja, Surrealist founder Andre Breton writes, “Who am I? If this once I were to reply on a proverb, then perhaps everything would amount to knowing whom I ‘haunt’.” Looking at Nedivi’s work, I wonder if we might invert Breton’s dictum. “Who am I? Perhaps everything would amount to knowing who/what haunts me.” The women of “Inherited Memories” are indeed haunted by inherited memories of the Holocaust.

Malka Nedivi, Inherited Memories, Castelli Art Space; Photo Credit Kristine Schomaker

For this viewer, the most poignant space in the exhibition is the pairing of two of Nedivi’s large sculptural works. One is a female grasping a small wraithlike child who reaches up with aching intensity to embrace her. Facing them is a tall, thin man, his heavy egg-like head bending wistfully to one side. The space between the two sculptures is fraught: I can feel them longing for each other, bending towards each other… and yet, they remain apart, alone and vulnerable. That sense of isolation and yearning must have been constant in the camps–and it must have been one of the emotional wounds carried by all of the survivors.

Harvard Professor Rita Goldberg has studied how many of her generation were “defined by their parents’ history, even though they did not live through it.” The realization led Goldberg to research and write about traumatic family experiences, specifically those of her Holocaust-survivor mother. She wrote a book on her mother to confront her personal demons. “I’m not sure it helped, but I never wanted to remove or exorcise these ghosts. They belong to me. I only wanted to examine and understand my relationship to them.”

Arbel, Fried, and Nedivi make art for the same reasons: They seek “to examine and understand” their relationships with their parents, their parents’ Holocaust past, and how it has impacted them. Those who also grew up with Shoah survivors can relate immediately. And all of us need to remember that there have been far too many atrocities that continue to affect victims and their offspring: not only the Shoah, but also the European slaughter of Native Americans and indigenous people on several continents, the Armenian genocide, the White Nationalist terrorism endemic to this country today, and the torturous existence of the families incarcerated on our borders. Those of us who haven’t suffered such traumas directly have a wondrous opportunity to practice empathy and compassion, and to do whatever we can to insure such abominations are not repeated.

There will be an artist talk Sunday May 26, 3-5pm. The last day to see the exhibition is May 28.

Castelli Art Space 5428 West Washington Blvd, Los Angeles, 90016

#losangeles #california #ShulaSIngerArbel #losangelesartist #art #painting #shoeboxpr #laverne #losangelesart #contemporaryart #holocaust #Peterfrank #southerncalifornia #abstract #collage #InheritedMemories #artgallery #kristineschomaker #artinterview #gallery #museum #artandcake #artexhibition #installation #fineart #bettyannbrown #artist #soloshow #mixedmedia #arts #artreview #artmagazine #ArtandCulture #exhibition #exhibit #DworaFried #malkanedivi #castelliartspace