“Spirited Away,” Belkis Ayon at the Fowler

- artandcakela

- Apr 20, 2017

- 5 min read

Installation view, Nkame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2016 Courtesy the Estate of Belkis Ayón Photo: Reed Hutchinson

“Spirited Away”

By Nancy Kay Turner

“We do not know enough about the unknown to know that it is unknowable.”

G.K.Chesterton

NKAME is the title of the retrospective exhibition at The Fowler Museum at UCLA that closed in February. The show introduced the haunting collographs of Cuban printmaker Belkis Ayon to new audiences. Though Ayon died in 1999 at the age of 32, her spectacular, spiritual and profoundly moving hand-pulled prints feel contemporary in style and theme. Ayon, a self-described atheist, choose to examine the language and symbols of the Abakua religion, which has only about 20,000 adherents. Established in 1836, there are only three Cuban cities where this secret society exists. Ayon said about this Afro- Cuban religion that, “I discovered that…no other artist was working on (Abakua), but on others such as Santeria, Voodoo, Spiritualist. There was a whole world that I could perfectly conceive starting from what I already knew”.

Installation view, Nkame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2016 Courtesy the Estate of Belkis Ayón Photo: Reed Hutchinson.

Most of the work in the exhibition is from the 1990’s. Ayon graduated from The Higher Institute of Art in Havana in 1991 and immediately began to have a national and international presence. As pointed out by Cristina Vives in her essay “Belkis Ayon Revisited ,“ the 1990’s were a difficult time in Cuba after the fall of Communism and the break up of the Soviet Union. As is often the case, it was a tense time for most artists as well. Because Ayon’s work was considered “ethnological” (relating to an anthropological examination of religion) her work was freely exhibited.

Upon entering this stunning retrospective exhibition some 18 years after her untimely death, one is struck both by the enormous scale of these collographs and the singular power of Ayon’s reliance on only the starkness of black, white and gray. There is a sense of being in a sacred space as well because of the nature of the installation. Some of Ayon’s epic scaled prints are installed like altars (these are not straight on their top edge but curved like a piece of wood). Other images are literally abutted on two contiguous walls at right angles. Some large collograph prints flow from the wall onto the floor, creating a literal pathway – an aisle, if you will, to the divine. All of this enhances the air of theatricality that often surrounds many religious practices (special clothes, headdresses, incantions, lighting, text, and procession).

Belkis Ayón, Sin título (Sikán con chivo) (Untitled (Sikán with Goat)), 1993 Collograph. Nkame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón Fowler Museum at UCLA, Photo Courtesy of the Fowler Museum.

The process to make a collograph print is especially complex. Collograph prints are hand- made from “plates” of cardboard or other substrates that the artist has altered. The surface is slightly raised when the artist affixes (glues) cut imagery, thereby creating a texture to hold the ink. The process itself is tricky — one cannot make the surfaces too high or else the ink will get stuck in the crevices and squish out when printed — and extremely time consuming. After the image is created, the plate is carefully inked, then wiped by hand to achieve pristine whites, nuanced grays and rich blacks. A damp piece of printmaking paper is laid carefully over the collograph plate and run through the press.

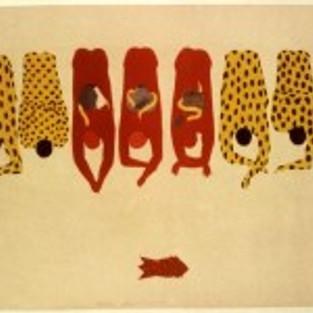

The technical virtuosity and religious content of the work is on display in “La Cena (The Supper)” (Collograph, 54” x 118”). This supper, though not Christian, has many elements of the oft painted Last Supper. There are ten androgynous humans, seen in silhouette, drawn with an elegant contour line (how does she do that with collograph?), six standing and four seated. Symbols abound here: there are fish (again a Christian symbol of Jesus Christ), and a snake wrapped around the only purely white figure (white represents death to the Abakua). The main figure stares resolutely ahead, while others recline, seemingly in boredom or perhaps because they are satiated. Figures behind Princess Sikan stand, peer, and offer to serve. With an economy of gesture a whole world is suggested here. Many of the figures are filled with elaborate designs that reference fabric patterns or African tribal body art. Ayon creates each image in sections. She prints separate full-sized sheets and then perfectly aligns them. This is a Herculean task and Ayon’s skill is unparalleled.

Belkis Ayón, La cena (The Supper), 1991 Collograph. Nkame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón Fowler Museum at UCLA, Photo Courtesy of the Fowler Museum.

The myth of the Abakua refers to Princess Sikan, who accidentally traps a magical fish that can bring peace and prosperity to anyone who catches it. She is immediately consecrated and must be hidden so others who want to possess the fish won’t capture her. She tells her boyfriend Prince Mokongo (big mistake) and it leads to her being condemned to death for divulging the secret. The magical fish dies and the diviner Nasako tries to recreate the fish’s voice by using the skins of a snake, a crocodile, deer and ram to make a special drum. After he failed, he needed Sikan to be sacrificed for her blood and skin. When this still didn’t work, the Diviner had to use the skin of a male goat instead.

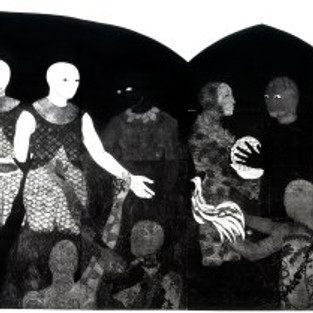

In “The Consecration I” (1991, collograph, 90.5” x 119 ¼”), we see Ayon’s interpretation of this story as Princess Sikan (in white) stands next to what may be the Diviner. There are actually two figures on either side of her—both with nimbuses and both with scepters or shepherd staffs. On Princess Sikan’s head is a rooster which is a symbol used by the Greeks as a sign of Apollo, Zeus, Persephone and Attis. The Hebrew’s have the word “gever” which means both “man” and “rooster.” This means that the animal can be used as a substitute for humans and sacrificed at Yom Kippur. And in Christianity, the rooster crowed three times as Peter denied Jesus and became a symbol of Christ’s passion. Roosters are often found in tombs, as the ancients associated them with the light, since they crow at the break of dawn. Loaded symbols like the rooster and the goats in this image and others here speak to death and perhaps to rebirth. Ayon’s figures have no gender – they all have no hair, and though rarely clothed – they have no visible breasts or phalluses. Their eyes are all simplified like Egyptian art -sometimes pure white with no iris or all black- almost like wooden religious statues. They are often frontal and parallel to the picture plane or only slightly turned, giving the composition a sense of formality and unreality.

Belkis Ayón, La consagración I (The Consecration I), 1991 Collograph. Nkame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón Fowler Museum at UCLA, Photo Courtesy of the Fowler Museum.

In the late nineties, Ayon made a series of smaller collographs enclosed in a circle. “Dejame salir” (Let me out)” (1997, 39 ¼” x 29 ½”) in retrospect may be a self-portrait of anguish and constriction. The female figure is shown hands facing us as if pressing against the glass. To a Westerner it actually looks like she is caught in the spin cycle of a washing machine. Seen through this circle, the figure looks desperate. Darkness may have been closing in. Ayon did not approve of the many psychological and religious interpretations of her work. But it is impossible to walk through this epic and eerie exhibit without getting chills down one’s spine. Ironically, in trying to create a new and original interpretation of a specific yet unknown religion, Ayon was able to connect the dots between ancient and modern religions, and ultimately blend their unique narrative seamlessly into a totally original and poetic body of work.

#losangeles #california #Cuban #art #exbiti #losangelesmuseum #FowlerMuseumatUCLA #LosAngelesArts #losangelesart #SpiritedAway #southerncalifornia #ucla #BelkisAyon #artgallery #artandcake #artexhibition #ArtandCakeLA #NancyKayTurner #printmaker #artist #artsmagazine #arts #artreview #artmuseum #artexhibit #ArtandCulture #exhibition #Nkame #retrospective #onlineartsmagazine #FowlerMuseum