With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985 at MOCA Grand Avenue

- artandcakela

- Dec 4, 2019

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 16

Miriam Schapiro, Barcelona Fan, With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985, MOCA Grand Avenue; Photo credit David S. Rubin

An Expansive View of an Underrated Movement: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985

MOCA Grand Avenue, Los Angeles through May 11, 2020

Written by David S. Rubin The Pattern and Decoration movement, or “P&D” as it is often called, was born in New York City in 1975, when a group of painters got together to talk about their shared affinity for incorporating decorative and ornamental motifs into their art. Some also employed techniques traditionally associated with crafts. At the time, these artists were out of sync with Minimalism, the reductive style then favored since the mid-1960s among high profile artists and critics. Essentially antithetical to Minimalism, P&D gained considerable attention over a brief period, as other like-minded artists were identified and numerous group exhibitions were spawned and written about in art magazines.

In her curatorial statement, curator Anna Katz observes that P&D was by the mid-1980s considered a passing fad. So, in this first ever comprehensive survey of the movement, Katz sets the record straight. In presenting works by artists directly involved as well as tangentially associated with P&D, the curator offers up an impressive gumbo that thoughtfully considers not only the movement’s usual suspects, mostly New York-based white female and a few white male feminists, but also sheds light on P&D elements in the work of artists of color and those working outside of New York, with many based in Los Angeles. Additionally, the exhibition explores influences of domesticity and non-Western cultures and, with the benefit of hindsight, makes it clear that P&D was one of the first manifestations of “maximalism,” which today is ubiquitous.

As might be expected in a survey exhibition of such broad scope, some artists fare better than others. Among the best known pioneers, the strongest moments belong to Miriam Schapiro, Joyce Kozloff, and Cynthia Carlson. Schapiro, who was active on both coasts, is represented by a dollhouse created with Sherry Brody for the landmark Los Angeles feminist exhibition “Womanhouse,” and two of her characteristic “femmage” paintings, variants of collage that use stereotypically female materials and are shaped like common domestic objects. In Heartland, which resembles the lid of a heart-shaped candy box, buoyant flowers appear superimposed over repeating geometric patterns, with the expressive effect seeming joyful and life affirming. When first shown, Kozloff’s painting Striped Cathedral may have been criticized for not using feminist materials (it is simply painted acrylic), but it is a stunner. Divided into vertical registers, the work pits several decorative sections against a lone minimal one at far right, creating a vibrant back-and-forth tension while also conveying the idea of P&D ganging up on Minimalism. Carlson, who spent much of the 1980s traveling the United States when invited to create site-specific installations of what she dubbed “sculptural wallpaper,” updated her 1981 installation Tough Shift for M.I.T., adapting it to MOCA’s space and rendering it in new colors. Occupying almost an entire gallery, the installation is characteristically playful, with the wallpaper’s floral motifs (made by squeezing paint through a pastry tube) dancing across the walls like animated living organisms.

Some artists in the exhibition, such as Frank Stella, would not consider themselves to be P&D artists. Nevertheless, Stella’s work was included in an early P&D exhibition. In “With Pleasure,” he is represented by one of his baroque polychromatic sculptures from the late 1970s. Al Loving, an African-American who practiced hard-edge abstraction in the 1960s, really shines with two mixed-media works that were inspired in part by his grandmother’s quilts.

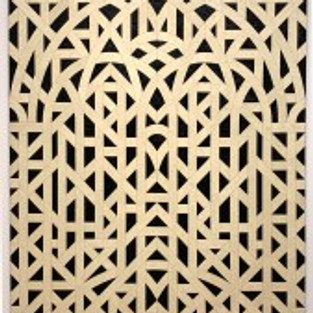

One of the benefits of survey exhibitions like “With Pleasure” is that they can bring overdue recognition to lesser-known artists. Notable examples include Franklin Williams, Arlene Slavin, Mary Grigoriadis, and Valerie Jaudon. Williams’ Four Made My World is a visual showstopper, a partially stitched painting that is at once vibrant, tactile, and enigmatic. Slavin, who is a self-avowed champion of “lush painting,” clearly demonstrates what she means in Raj, where a sparkling luster results from the rich saturation of jewel-tone paints used to create an allover pattern of overlapping diamonds and triangles. Patterns in paintings by Grigoriadis and Jaudon derive from architectural sources and are thus devoid of feminine associations. Both artists appear here as rigorous painters, accomplished masters of composition and technique.

From a local perspective, Angelenos in the exhibition occupy a forceful and meaningful presence. Neda Alhilali is represented with Pearly Gates, a groundbreaking paper painting that effectively simulates a Jackson Pollock style allover surface. Alhilali’s innovative process was to paint a support that she constructed by braiding, knotting, and weaving together moistened paper and running it through an etching press. Merion Estes’ Primavera is a jubilant homage to spring that employs a kitschy aesthetic reflecting her longtime admiration for Mexican, Native American, and Spanish Colonial textiles and crafts. Constance Mallinson’s colored pencil drawings of the early 1980s could be called the most restrained and, quite frankly, most minimal works in the exhibition. Yet, with this early body of work, Mallinson proves so eloquently that often there is more than meets the eye. Looking closely at her seemingly monochromatic drawings, we discover meticulous replications of fabric as if viewed under a magnifying glass. In this respect, these works are aptly metaphoric of one the exhibition’s most insightful messages: Never take anything at face value. Dig deeper. There may be unexpected pleasures to be found.

Museum of Contemporary Art 250 South Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, 90012

#losangeles #california #losangelesartist #MiriamSchapiro #ArleneSlavin #art #painting #shoeboxpr #laverne #CynthiaCarlson #losangelesart #contemporaryart #FranklinWilliams #NedaAlhilali #southerncalifornia #MOCAGrandAvenue #ConstanceMallinson #abstract #collage #FrankStella #merionestes #artgallery #artinterview #AnnaKatz #gallery #museum #JoyceKozloff #artandcake #artexhibition #installation #fineart #DavidSRubin #artist #soloshow #mixedmedia #arts #MaryGrigoriadis #artreview #artmagazine #ArtandCulture #exhibition #exhibit #ValerieJaudon